Rocky Mountain News (CO)

Rocky Mountain News (CO)

May 10, 2003

WORLD-CLASS MOMS

Edition: Final

Section: Home Front

Page: 1A

IN HOME FRONT / A breakfast of soggy french toast and burned bacon, served with pride on a makeshift breakfast tray. A dozen red roses, stuffed into a too-small vase. Those are things moms expect on Mother’s Day. But one Aurora mother envisions finer gifts this year. Tammi Roberts will spend Sunday in a hospital, offering comfort to her daughter, Brianna. She’ll hide her fear, as she has for months, and encourage her daughter to stay strong. The gift Tammi wants most for Mother’s Day is intangible. She wants her sick daughter to live a long, healthy, happy life.

A MOTHER’S STRENGTH

3-YEAR-OLD WITH RARE CANCER PUTS MOM’S FORTITUDE TO THE TEST

Author: Debra Melani

ROCKY MOUNTAIN NEWS

Page: 1E

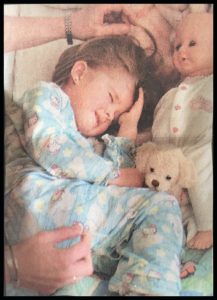

Brianna Roberts grins as her mother hands her a carefully wrapped package. In a moment, paper crinkles and ribbons fly; the gift has clearly been ripped open by a pro.

“Another Barbie!” the 3-year-old exclaims, cupping her hand over her mouth as if to stifle a giggle. Her mother smiles and ruffles her light brown hair. “Yeah, that’s nice,” Tammi Roberts says.

This is no festive birthday celebration. The gifts are from a Greeley kindergarten class, and Brianna is perched on a hospital bed, awaiting nurses who will take her away at any moment.

Brianna is about to undergo major surgery. Chances are only 50-50 that it will stop the rare cancer growing in her abdomen.

“We don’t know if we have her for five more years or five more months,” Tammi says.

Yet she remains stoic.

“I’m not going to cry in front of her,” the Aurora mother says later. “That wouldn’t do her any good. If I’m strong, she’s going to go into surgery stronger and with a better frame of mind.”

Like any other day, Mother’s Day will find Tammi keeping a vigilant watch on her daughter’s health. As with other moms with a child facing life-threatening illness, her battle is exhausting, testing her strength in all the traditional roles: from wife to mother to her child’s protector.

Tammi’s challenge began three years ago, when intuition told her Brianna’s doctor was wrong. She refused to take the small mass she found in her baby’s diaper lightly.

“He said he didn’t know what it was, and he wadded up the diaper and threw it away,” says Tammi, 30. He then told her they should wait to see whether it happened again.

“No, I am not waiting,” she answered.

Tammi and her husband, Gene, insisted on more tests, which revealed a tumor in their 9-month-old girl’s vagina, a rare cancer called rhabdomyosarcoma.

The disease is more common in children than in adults. Brianna’s form, which began before birth, strikes infants more frequently in the head and neck than in the reproductive organs.

“The hardest part is not knowing the future,” says Gene Roberts, 36, who says his wife has remained strong for the whole family, which includes 11-year-old Janaya Poor from Tammi’s previous marriage.

“We don’t have the answers. The doctors don’t have the answers,” says Gene, who has, at times, worked three jobs to help pay the medical bills and allow his wife to remain a stay-at- home mom for the girls. “We have a 50-50 shot, which aren’t terrible odds but still aren’t very good.”

For Mother’s Day, all she wants is to be in that lucky half, Tammi says. “I just want a cure.”

Fight from the start

“Run upstairs and play,” Tammi tells Brianna on a recent spring day. The two have just finished a backyard picnic. A video camera sits on a tripod next to the door.

Following her mother’s orders, Brianna bounds off, climbing the stairs with both feet and hands, her bottom sticking up in the air. The high-spirited 3-year-old, only days away from major surgery, hardly appears ill.

When she was diagnosed at 9 months old, Brianna went through aggressive chemotherapy that made her very ill. A family photo, taken in a rush at Tammi’s urging, includes a smiling baby, bald from the chemotherapy; it hangs in the upstairs hallway of the Robertses’ suburban home.

But the treatment was successful, and Brianna lived cancer-free until just before her third birthday.

That’s when her mother’s recurring nightmares began.

“I’d had three dreams in a row where I lost Brianna,” says Tammi, who has been patiently redirecting her little girl upstairs, not wanting to upset her with talk about the illness.

Soon after the dreams, Tammi noticed that Brianna was using the bathroom nearly every 15 minutes. The fear struck again.

Then the disbelief.

Like an eerie replay, a doctor told Tammi it was probably nothing to worry about: either a normal phase in her development or a bladder infection. “Let’s wait six weeks and see if it goes away.”

Delayed diagnosis of childhood cancers is common, says Brianna’s surgeon, who saw her after her cancer was found.

“The bottom line is that common things happen commonly, so why would you assume the worst?” says Dr. Peter Furness of Children’s Hospital. Symptoms of many childhood problems mimic those of cancer, Furness says, adding that a six-week delay in diagnosis wouldn’t necessarily make much difference.

But Tammi refused to wait, insisting on an imaging test. It showed a tumor the size of a large lemon that this time had grown beyond the vagina, invading Brianna’s uterus and pushing on her bladder.

“I felt like I’d been stabbed,” says Tammi, sitting on her living-room couch, her short black hair framing a weary-looking face. She cried alone every night for two weeks, she says.

Stories like Roberts’ aren’t unusual, says Valerie Baker, who heads a Longmont support group for mothers of children with brain tumors. In fact, finding a doctor to take her own son’s headaches and vomiting seriously more than 10 years ago was hard.

She finally persuaded a physician to send her to Children’s Hospital in Denver, where the tumor was found. “My teeny little boy looked up at me and said, ‘Gee, Mom, it doesn’t hurt so much now that they believe me,’ ” said Baker, whose son survived the initial treatment and a recurrence and is graduating from college this spring.

For Roberts, who says she’s indebted to Children’s Hospital and Brianna’s oncologist, protecting her child’s health didn’t stop in the doctor’s office.

An instant nurse

“Ouchie, Mommy! Ouchie, Mommy!” a curled up Brianna screams, her little face contorted in pain. Private in-home nurses have come to the Robertses’ house to help with the first round in a series of chemotherapy treatments. But they didn’t connect the catheter to the port correctly.

“Ouchie, Mommy! Ouchie, Mommy!” a curled up Brianna screams, her little face contorted in pain. Private in-home nurses have come to the Robertses’ house to help with the first round in a series of chemotherapy treatments. But they didn’t connect the catheter to the port correctly.

Once the mistake is noticed, the potent drugs have created a bulge on Brianna’s chest, entering just beneath the skin instead of into her veins.

Inside, Tammi is fuming. But she remains calm, comforting her daughter after the ordeal. She forbids any more attempts at therapy and rushes Brianna to Children’s Hospital to be examined instead.

“No, I never imagined I’d be giving someone chemotherapy,” Tammi says later. “But I’d rather do it myself. And she doesn’t want anyone else to do it.”

Chemotherapy drugs can be acidic and burn tissue, said John Carlson, founder of Zac’s Legacy Foundation, which provides educational and support services for families of children with cancer. The foundation is helping the Roberts withstand the cost and trauma of chemotherapy treatment. The Roberts’ insurance covers only some of Brianna’s care.

Moms of kids with cancer are often forced to become in-home nurses, says Debbie Carson, executive director of the nonprofit organization. “It adds to the stress,” she says. “They feel like, ‘What if I do something wrong?’ ”

But in many cases – especially Brianna’s – children prefer to have Mommy do the scary things.

Brianna and her mother have a strong relationship, Gene says. Brianna reaches for her mom whenever she’s sick, tired or in pain – which is sometimes nearly 24 hours a day, he says.

“Even in the mornings or at night, if she’s just a little cranky, she doesn’t want me. She wants Mommy.”

Brianna’s dependence on Mom is common, says Erika Sandstedt, a social worker at Children’s Hospital, who has helped the family through both of Brianna’s illnesses. “You fall down, you get hurt, you want your mommy.”

With cancer treatments often lasting a year or longer, playing caretaker while hiding their own fears can be exhausting for moms, she says.

Tammi doesn’t argue that point. “Sometimes I can’t even focus,” she says. “I don’t know where it comes from, other than you have to do it. You have to keep going.”

A challenged parent

Brianna sits on the floor of her bedroom, the bright yellow walls accented with Winnie the Pooh wallpaper and a large, hand-painted tree that “Mama” painted.

Brianna sits on the floor of her bedroom, the bright yellow walls accented with Winnie the Pooh wallpaper and a large, hand-painted tree that “Mama” painted.

It’s past nap time, and Brianna is transfixed by a Blue’s Clues episode playing on a small, pink television set. Amid dolls, stuffed animals and other Barbie toys, she sits motionless, except for one finger methodically twirling a Barbie doll’s hair.

Every day is an emotional struggle, Tammi says.

Brianna often tests her mother with questions: “Why do I have to have a hole in my chest?” “Why do I always have to go to the hospital?”

She informs her mother that her friends never have to go to the hospital.

“I just tell her it’s what her body needs,” Tammi says. “We tell her she’s special.”

Brianna isn’t Tammi’s only mothering challenge. Janaya, her older daughter, often feels left out.

“It’s hard. She says it’s not fair that everything has to be focused around Brianna,” Tammi says.

But parents have no choice; life does have to be centered on Brianna, says Sandstedt, who runs a summer camp for siblings of children with cancer. “Tammi’s life is about Brianna right now. No matter how hard she tries to divide her time, it’s not the same,” she said.

Siblings suffer in many ways, Sandstedt said. Their parents miss soccer games, their birthdays are postponed because of treatments, they fear losing their sibling, they worry their parents will get sick from exhaustion.

“Janaya won’t be with her mother for Mother’s Day,” says Sandstedt, knowing that Brianna and her mom will be in California undergoing what Tammi decided was the best radiation treatments she could find.

Guilt can plague parents; anger and hurt can well up in siblings.

“But unfortunately, that’s what has to happen sometimes,” Gene says of missed special occasions. “Brianna’s care is just more important than anything else. We certainly talk about it, and understand that it’s hard, and agree that we’ll celebrate it later.”

Test of strength

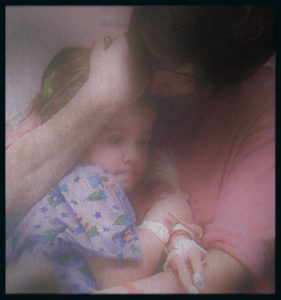

Surgery will begin soon. After the long wait, which involves tickling, giggling and quick kisses on the head, Tammi carries her little girl across Children’s Hospital.

Surgery will begin soon. After the long wait, which involves tickling, giggling and quick kisses on the head, Tammi carries her little girl across Children’s Hospital.

She sits down and holds Brianna in her arms as nurses administer sedatives. She smiles at her, whispering in her ear and hugging her tightly as the little girl begins to fall asleep.

Tammi’s strength is good for Brianna, Carson said. Parents don’t want their child to be scared or feel guilty for causing the stress that has crippled the family.

“She’s amazing,” Carson said, adding that all the moms she works with are like that. “They have to be brave. It’s the only chance that their child has. They aren’t going to do anything on earth to hinder that.”

Baker recalls when the doctors told her that her son’s tumor had recurred. She held her breath and repressed her emotions. “I remember my little boy looking up at me. I kept myself completely together because he was studying my face.”

Soon, Tammi stands, cradling her 3-year-old in her arms like a baby. She gives her one last kiss on the cheek and hands her to the nurses.

Relatives watch from behind, unable to stop the tears. But Tammi doesn’t cry.

Her strength doesn’t surprise her husband, who says that after five years of marriage, he’s seen her courage.

After a daylong wait, the Robertses hear the surgery went well. Brianna lost her uterus and half her bladder, but doctors were pleased that the other half of the bladder and all of the colon were saved.

“Go home and tell your wife tonight that you’re my hero,” Tammi tells Furness. Gene brushes away tears.

Although the future is uncertain, the couple says they’ll keep loving – and fighting for – Brianna.

“It puts everything in a different perspective,” Tammi says. “You don’t care what you drive, where you live, what clothes you wear.”

And she doesn’t need a Mother’s Day to remember how special her girls are, she says. “I cherish them every moment of every day.”